The Great American Going Out Of Business Sale

a long reflection on physical media, what music means to me, how I got here, and gifts

If nothing else, holding a Ziploc bag containing the charred bits of my favorite album brought new meaning to the term burnt CD.

I was in the 8th grade in 2000. My favorite album in the world, Dillinger Four’s Midwestern Songs of the Americas, came out two years earlier. How did I get into this midwestern punk band at 12? How did I get my hands on the CD in the first place? And why had I just been handed an object that looked like it’d been recovered from a house fire? Telling this story feels like locating the person I am today in an atomic moment.

Napster’s part of it, for sure. I definitely stole music, and had no money. But there was one momentous afternoon when I did.

I bought a compilation album at the mall, on a whim (and on the recommendation of my friend Ian Blackman — Ian, if you’re reading this, I hope you’re doing okay), that comp being 1999’s Short Music For Short People. I complained to Ian that I needed some new bands in my life; he pulled this CD off the rack and said, “Well, this one has 99.” Which, at the time, might as well have been all of them.

99 bands, 99 songs, all thirty seconds or less. And D4 was track 18: “Farts Are Jazz To Assholes”.

Yes, I’m admitting to you that the song that changed my life the most is called “Farts Are Jazz To Assholes”.

It was unlike anything I’d ever heard before. Listening to it now it’s still totally clear, to me, what would have distinguished it from other, more radio-friendly pop-punk. It was every bit as tuneful, but more raw, for sure. But more than that, Erik Funk sounds so believable to me, so sincere. Not sneering for the sake of sneering, not over the top, but genuinely taking the piss. Irreverent as hell — again, they named it what they named it — though interestingly, not towards the music, which is played with both muscle and finesse. There’s genuine craft and musicality: these wonderful little rhythmic bait-and-switch moments, the same borrowed chords that I’m obsessed with now, years before I understood them. There’s more than a few voices in the mix, there’s handclaps (we all know that backing vocals and handclaps means it’s a hit) and it’s all so spirited. When he sings “I don’t care, so do your worst, ‘cause I’ve got nothing to say” it sounds triumphant, like spitting in the face of a bully when they try to pull some “any last words?”-type shit before kicking your ass, a feeling I’d experienced firsthand by then.

By then I had Napster, and I downloaded every Dillinger Four song I could. And the others? They were, miraculously, longer than 30 seconds! And richer, and deeper! And sounded just as raw, and there were different singers on different songs! And they still had provocative titles: “Fuck You, Ms. Rochelle”. (Who’s that!) “An American Banned”. (What for!) “Thanks For Nothing”. (Felt that!) “Twin Cities Sinners, United”. (Tell me more!) And that was just the More Songs About Girlfriends and Bubblegum 7”, which, one, I didn’t know what a 7” was, and two, I barely knew what irony was. But it was exciting.

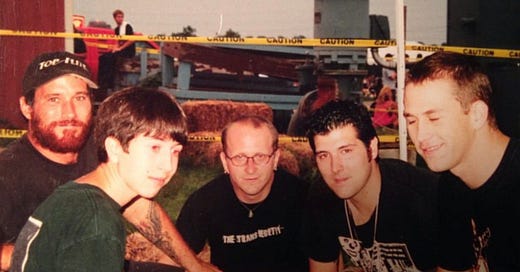

The official Dillinger Four website was hosted by angelfire, and hilariously, marvelously, it still is. Their site is how I found out that this band was playing in Connecticut, a few hours away, at the El-N-Gee in New London. I was not yet fourteen, so I had to beg my mom to drive us out there, and – praise God and pass a bottle of Beam – she obliged me.

This show, I realize now, was twenty-five years ago. And these dudes were not even in their thirties yet.

They played the show with a local opener whose name escapes me; that band played first, then D4. After them were Leatherface and Avail, two bands who would later become favorites of mine, too, but we had to leave after D4. (It was two hours away and I was a child.) I don’t remember much specifically about it, honestly, other than that Paddy was perhaps sick – perhaps hungover – and they played a short set. But no part of me was disappointed. In a strange way, this was like a holy pilgrimage; even only going a few hours outside the suburbs felt like being halfway across the world. Certainly far enough to feel like I’d left my world behind.

This music that only existed on a disc or on my parents’ computer was now in front of me, in the flesh, loud and present. I took it in along with, at most, twenty others. My mom gave me money to buy whatever CDs I wanted. When we got home I removed the plastic and finally heard the albums in their proper glory; I devoured the liner notes, pledging to check out all the other bands D4 listed in their thank-you’s — Scared of Chaka, tiltWheel, Panthro U.K. United 13, Small Brown Bike, Hot Water Music, more that I can’t begin to remember now1 — and cherishing these physical documents, this manifestation that proved I’d entered a new world, that I’d taken some of it back with me, so that I’d never have to leave.

Something about the idea of this band, to me, represented deep, abiding friendship, or even brotherhood. The image of four guys literally banding together, giving each other flowers, building up this myth of one another — maybe Lane Pederson was a PhD, a trained DBT therapist and author (and undeniably brilliant guy) in the eyes of the world, but in this world – the world of the album sleeve, anyway – he was Monkey Hustle; Patrick Costello was St. Paddy; Erik Funk was “the sexy marketing tool.” These were guys propping one another up to be greater than they could be alone. And I felt really alone then, and needed to know I didn’t have to be.

I must have given the album to Matt and Griffin to borrow it. The motivation must have been simply wanting to share it. They could have just downloaded it, but this way, the files would be at least 192 kbps, and the song titles would be correct, and with D4, that was both essential and a big ask. We’re talking about an album with titles like “Superpowers Enable Me To Blend In With Machinery”. And to my young, obsessed mind, those details were essential. Even a little laziness in the file-sharing community would have tainted the whole thing. If you changed any one word, it wouldn’t be right, it wouldn’t be them. The disc, the notes, the art, that was the real deal, was everything. This was a prized possession, a rare artifact that had been hard to come by.

I don’t know what they were thinking, only that they must have thought it through. It would have been one thing to just break it, cracking the disc and tearing the pages of the booklet; this was different, the definition of pre-meditated. They had it in their possession long enough to weigh their options, to decide exactly how they wanted to disfigure this album. So they devised a scheme to light the thing on fire, to burn it to a crisp, and return it, this attempted gift, as charred bits, destroyed parts, broken, blackened and melted plastic, unplayable and irreparable.

Even now I’m struck by the casual animosity, the banal cruelty, of the act, and the way it bonded them. They did it together, as friends.

The cover of Midwestern Songs of the Americas depicts an American flag blown by a box fan, hanging like a curtain from a window in crisp, dappled light. The way bright patches of light are caught in the flag make it appear to be burning. The sun is either rising or setting; it’s not entirely clear.

The back cover of Midwestern Songs of the Americas depicts a splayed bloody hand casting a dark shadow against the body of a Rickenbacker bass, blood in a violent pattern splattered across the white pickguard. Beneath that, a snare drum with an American flag sticker on its head.

The color of the Rick’s body – its bloodless portion – is, fittingly, sunburst.

For my whole life I’ve been uncomfortable with the idea of marking up my books. At most, I’d dog ear a page, always folding it back as I moved along; I relied on bookmarks, actual or makeshift, in part to help prevent the need to deface anything. I wanted my books pristine. Only recently have I embraced underlining, writing or drawing in the margins. It took me long enough. I have to think it was fear-based: fear of making choices I’d regret, of embarrassing myself, of judgment and reprisal and rejection. As much as I’ve claimed to not care about those things, and meant it, something about the thought of altering books stopped me in my tracks, stopped me from making marks.

In the past few years, I’ve gotten into putting silly bumper stickers on my car and getting not-terribly-significant tattoos. When I was in high school, I thought I might get the Avail logo tattooed on one ankle, the Hot Water Music tattooed on the other. It never happened. Those would have been significant, but maybe too significant. (I kind of only started doing it recently to prove to myself that I could, that redefining myself, even permanently, was an option always on the table.) And still somehow the idea of getting permanent ink on my body was more acceptable, less uncomfortable than the thought of underlining a passage I like in a book. Maybe it’s because I didn’t write the book, and it feels intrusive. I can do whatever I want to my body or my ride, but someone else’s labor, or art?

But memorizing is something else altogether. In my mind, many lines from Midwestern Songs are single-, double-, and triple-underlined, for life. This is true despite the fact that I’ve only listened to it a handful of times in the last ten years. I carry so much of it with me. Here’s some, plenty, of what’s most resonant, known by heart:

Let’s tie a yellow ribbon ‘round the necks of the motherfuckers living for the giving in

I saw it coming, now it happens all the time / First you had a DIY chip on your shoulder, then you got an ego fifty fanzines wide / (Don’t give me those eyes!) / That confidence you’re selling, I won’t buy / Maybe the costume fits, but the script’s still shit.

Mother said I can’t listen to Radio Havana / I read by a flashlight late that night

Father wasn’t picking sides / But dog-eared pages gave clues to the thoughts inside2

I don’t understand spending life ignoring / The other side of the story

D! 4! (Paddy singing) Sometimes simple things that make it hard / Spoiled baby tee’s and credit cards / Overtime always on my mind / Could-have-been’s eat away inside, now / Praise God and pass the bottle of Beam / ‘Cause I never can seem to say what I mean / Don’t know if I would, even if I could / “Amen” / Somehow this feels like borrowed time / Pay no mind, everything is fine / But sometimes I’d rather hear laughter while this whole place dies / A Johnny-Jump-Up is a lovely thing / A pint of cider and some whiskey / I had four dead inside of me3 / Just to hear this jackass sing his line about / How he used to hang out / Somewhere back in the day / Knowing terms only an asshole would say / So I sat there drinking more, thinking ‘bout drinking more.

Nelson Algren came to me and said, “Celebrate the ugly things” / The beat-up side of what they call pride could be the measure of these days.

(sampled recording of Otis Redding speaking) Hi! This is the Big O! I was just standing here, thinking about you, and thought I’d write a song about you! Take a listen!

(Erik singing) God save Otis Redding, ‘cause I know he’s never gone / And as sick falls from this mouth, hear me sing it wrong / Is it “Cigarettes and Coffee” now or “Dreams to Be Remembered”? / I’ll leave regrets for dead and sing along.

(Paddy singing) Now I’m reaching for the phone, I don’t wanna be alone / I’m gonna get some friends here tonight / I got a basement full of booze and some blues to lose / I’ll ignore the whole world tonight. It’ll be alright.4

All these specters of the workplace turn from effigy back to reality / And I wish it was that simple, to think a belly laugh is really all we need / But it’s the slow decay of the day-to-day that says “Take your paycheck, accept your place and fade away” / But there was dignity in plastic seats that day

The judge who sent me up made a good impression for the next election / But what the media won’t say is, even with my freedom / I still wouldn’t be old enough to vote against the man

(Paddy singing) Is freedom just a privilege of hatred guaranteed? / (Billy singing) Is compassion just a second thought of hope brought to its knees? / (Paddy singing) Can dignity see fit to work past all it doesn’t want to see?

(quoting Billy Bragg’s “Waiting for the Great Leap Forward”) “Mixing pop and politics, he asks me what the use is?” / I’m not into making excuses / And I’ll die the day I find I’m fucking useless.

What strikes me now, as I’m writing this, is the way these words imprinted themselves on me through an unconscious underlining: the way singalongs beget memories, the way the memories sing themselves again and again, pressing deeper and deeper trenches in your psyche, pressed so hard even the unmarked pages underneath bear the impression.

While I was busy in front of the stage at the El-N-Gee, letting my mind get blown by this pop-punk band from the Twin Cities, my mom was at the bar, making a new friend. She was chatting up another woman there, who happened to be dating Joe Banks, Avail’s guitarist, at the time. They became sort of friends for a time; after D4’s set, Joe dropped by the bar to talk to us. Over the next 5 years, I would go — usually with my mom, but not always — to see Avail at least once or twice a year. Whenever possible, basically. This was indicative of the way the older women in my life shepherded me into this world; they recognized my interest and passion for this music and facilitated my safe engagement with it as a kid. It was my mom who flew us down to Krazy Fest, in Louisville, Kentucky, in the summer of 2001; it was my mom who bought 30-racks of beer for the bands as a bartering chip to get us backstage so I could watch the bands up close, without risking getting my head split open on the concrete with everyone else. This, more and more profound to me with every passing year, was mothering.

At Krazy Fest that year, I got to feel what it would be like to have older brothers looking out for me. (I have one older sister, no other siblings.) I met Hot Water Music, a band I’d fallen in love with largely because their gruff, bear-hugging songs were about community, care, mutual aid, friendship, love, responsibility — it was masculine music with unbearably tender themes. Their brand of emotional politics resonated with me as a kid for reasons I still don’t totally understand.5 We sat at a picnic table and talked, already heroes to me, and to my wide-eyed bewilderment, they gave me a copy of every single one of their vinyl records (and they had a ton by then). It was a kindness, a gift, that I’ve never forgotten, never quite gotten over, at best hoped to repay in my own way, with my own songs, knowing I’ll have to embrace merely trying, likely failing spectacularly.

There was a great tent in the field where labels and distros were set up, swelling with physical media: CDs, records, zines. I was leafing through rows and rows of albums between sets and struck up a conversation with a guy about ten years older than me named Ross. Mostly I remember he was intrigued by the fact that I was only thirteen, but wearing a Hüsker Dü shirt — “How do you even know who that is?” he asked. By the end of our chat, he’d offered me a shot at writing album reviews for his nationally-distributed alternative music zine, Law of Inertia. Over the next few years, Ross gave me a lot of valuable advice and guidance on how to take music seriously and how to write about it well, before he let me go for (probably) not taking it seriously enough and (definitely) not being that good of a writer. I was paid in free CDs, and it was a dream.

I haven’t heard from Ross in close to 20 years. I hope he’s doing okay.

I am writing this right now from a coffee shop in Brooklyn. Most of my physical possessions are in a storage unit in Philadelphia. The rest is in my car or in my friend’s apartment in Bed Stuy.

I’m thinking about the physical exchanges that these anecdotes depict and capture.

A kid, waiting for a box of CDs to arrive so he could sit in his room, listen, and write. A kid, holding the Ziploc bag his classmates just handed him, confused and hurt. A kid, sitting with one of his favorite bands on a hot afternoon, sunset not far off, far from home in Kentucky. Feeling the weight of a stack of vinyl records, freely given.

The funny thing — or just the strange thing — is I don’t have any of these things left. The torched D4 album? Long gone.6 (I still need to replace it — preferably on vinyl this time — but as you probably gathered, now’s not the time for me to be gathering.)

Those reviews for Law of Inertia? I think I still have old issues of Punk Planet in a box somewhere, but none of LoI. There might be a digital archive (I hope), but I’ve never found anything I wrote for them. Most, if not all, of the CDs they sent me are scattered, maybe gone forever, maybe waiting to be rediscovered in my parents’ attic.

Those Hot Water Music records I so cherished? This one stings a little: a few years later, in a bout of sadness, I gave away my whole vinyl collection, which by then was significant. Entirely to friends and loved ones. I don’t remember why. All I remember is that it felt necessary, and it felt permanent. Whatever I was so sad about is gone now, too.

We are physical beings, and so memories, despite prominent, durable metaphors to the contrary — fogginess, things disappearing like smoke, all that — are in us and on us, like physical presence, like marks. I can’t touch them as if they’re apart from me because I am them. There is real mystery at play when it comes to what you can reach or recover and what is or is not there. I move through the world with all that has obliterated and remade me, now and always.

I worry in the modern way about the effects that daily deluges of information are having on my mind and body: too much stimulus, too much content, too much sound and image. I worry not because it’s too much, but because it’s not nearly enough.

Because I still want to care so much about a silly band — a band with song titles like “Honey, I Shit The Hot Tub.” for fuck’s sake7 — that I’ll do whatever it takes to see them play; I want to buy everything they’ve got and then give everything I’ve got back to them; I want to spend hours on end on the floor of my room listening to the songs, staring at and thinking about the photos printed on matte paper in the booklet, like I’d discovered life on Mars; I want to wonder ad nauseam about who are these bands they’re thanking in the notes — their friends, they have so many friends — asking what on Earth a band named Scared of Chaka might sound like and not immediately finding out.

And I want to send that gift along to someone else, even if, no especially if, there’s a real chance they might turn around and kill me. That’s being alive, isn’t it? Holding things, touching things, being held and touched; making your own memories, becoming the self who remembers, who breathes this love back out, whose life becomes synonymous with the gifts they’re given again, and again, and again.

Turns out those were in the Versus God liners, tiltWheel rendered as Tiltasswheel just for kicks.

Hmm.

Tonight my friend Connor pointed out to me that this is likely a reference to Neil Young’s “Ohio”, something that definitely went over both our heads until now. After all these years, we’re still finding new things in these songs.

6-10 is all one song. The process of typing this one up from memory gave me chills and got me a little glassy-eyed (several moments get me without fail — “as sick falls from this mouth, hear me sing it wrong”). “Doublewhiskeycokenoice” doesn’t sound like much else I listen to anymore, but it’s still far and away one of my favorite songs forever. It contains so much heart, camaraderie, vision and love that I feel like I almost can’t bear it.

It doesn’t matter who you are or where you work / It doesn’t matter who you are or what you earn / What matters is what you give and what you love / What matters is how you live and if you love

This story eventually reached the band, or at least Paddy. Eventually I need to write a long piece about Scott Puckett and the impact he had on my life; suffice it to say here that Scott’s zine Sick To Move and his website, and conversations we had about music, art and politics, had an immeasurably huge impact on a very young me. (And we’ve still never met!) D4 was hugely important to him too, and I helped him track down their email address to request an interview; you can read his interview with Paddy, probably from early 2001, here. Scott told Paddy the story but got some of the details wrong, not that it matters now.

“Celebrate the ugly things.” D4 taught me that to lose the crudeness was to miss the point entirely, a lesson that feels all the more important now, in our age of frictionless, formless media consumption.

I caught that D4/Leatherface/Avail tour in Corona and it feels like forever ago. Shame you couldn't stay for the last two bands. They were kinda okay ;)